The yield point represents the point at which the internal structure of the manufactured part has reached its maximum allowable deformation under load. Engineers use this knowledge when designing new equipment to prevent equipment from failing during real-world applications including but not limited to construction and automotive manufacturing, as well as aerospace and industrial machine design.

What is Yield Point?

The yield point is the specific point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the plastic deformation in a material. Below the yield point, a material deforms elastically; it will return to its original size and shape. Once the stress exceeds the yield point, the material begins to deform plastically, resulting in some fraction of permanent, non-reversible change in shape or size. Before it reaches this stage, a material is elastic; hence, it will assume its original shape once the material has been taken off or the load is removed.

How Yield Point Works-

Yield point occurs at the end of elastic behavior and at the beginning of plastic deformation. The yield point typically has a dramatic change in the behavior of stress-strain curves, with much lower increases in stress resulting in large increases in strain. At the yield point, the stress level has resulted in dislocations within the atoms of the material moving from a fixed position to a new one. Hence, the yield point is important for the design of structures so as to avoid failure.

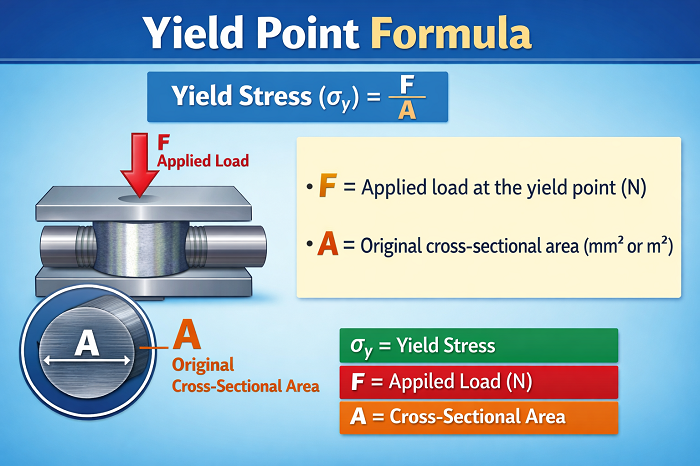

Yield Point Formula

The fundamental yield point formula is -

Yield Stress (σy) = F / A

Here,

F = Applied load at the yield point (N)

A = Original cross-sectional area (mm² or m²)

How to Determine Yield Strength

To accurately determine the yield strength, several essential steps must be undertaken such as preparing the specimen, measuring its original dimensions, and securely mounting it in the Universal Testing Machine (UTM). Later stages include applying a progressive tensile load, computing the stress-strain relationship, determining the yield point, and introducing a 0.2% offset if no distinct yield point is found.

Specimen Preparation

Prepare a standard test specimen using a cutting and machining operation as per ASTM/ISO standards. A smooth surface, gauge length, and alignment marks should be ensured. Defects due to machining and scratches on the surface may affect the result.

Measure Original Dimensions

Use calibrated calipers/micrometers to measure gauge length and cross-sectional area (diameter/thickness). Note readings and temperature. These reference values are then used to calculate engineering stress and strain; small discrepancies will result in considerable error in yield strength.

Mount the Specimen in UTM

Position the specimen concentrically within the sample grip area on the Universal Testing Machine. Zero all instruments. Check that there are no preloads and no alignment issues. Attach an extensometer for measurement of gauge length, if it is going to be measured.

Apply Tensile Loading Progressively

Apply tensile forces at a controlled rate of strain. Measure forces and displacement. Note the regions where MTFs deviate from the normal region. Continue applying forces at a constant rate. Stop at either breaking points or at specific strains. Record raw tension vs. displacement curves.

Calculate the Stress–Strain Relationship

Convert loading to engineering stress (σ = F/A) and elongation to engineering strain (ε = ΔL/L?). Plot stress vs. strain. Look for an indication of a yield point and read stress at that point as the value of yield strength.

Use a 0.2% offset.

If no clear yield A line parallel to the elastic portion with an intercept of 0.002 strain units (0.2% offset) should be drawn if no clear yield point occurs. It is the line of the intersection between this line and the stress/strain diagram that could translate to the 0.2% offset yield strength.

Yield Point and Stress-Strain Curve

The yield point of any stress-strain curve reflects the position of the boundary separating elastic or reversible dislocation of a material from plastic or permanent deformation. It is typically shown on ductile materials, such as steel, as a sharp decline in the slope of the stress-strain curve. This indicates that the high strains will only require very low increases in applied stress. Brittle materials do not generally have a clearly defined yield point, as they tend to fracture in an elastic state, typically at or very close to their elastic limit; when plotting applied stresses against deformations (Y-axis) (X-axis), this provides insight into the material's mechanical behavior.

The Stress-Strain Curve Explained

This graph shows the behavior of a material when it is subjected to increased load, which then reflects the main regions:

-

Elastic Region (O to B): Stress is proportional to strain (Hooke's Law), and the material, if it is unloaded, will revert to its original shape, e.g., points O to A.

-

Yield point: the point beyond which linear elastic behavior ends and plastic (permanent) deformation begins.

-

Yielding/Plastic Region B: The material stretches with relatively little further increase in stress; upper and lower yield points for steel can be observed—permanent change has occurred in the material.

-

Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) (D): The maximum stress the material can withstand before it begins to "neck" (localize thinning).

-

Point of fracture (E): Point at which the material fractures.

Yield Point vs Yield Strength

|

Parameter |

Yield Point |

Yield Strength |

|

Meaning |

The exact stress at which a material starts permanent (plastic) deformation. |

The stress needed to produce a small, measurable permanent deformation (usually 0.2% offset). |

|

Appearance on Curve |

Seen as a sudden drop or plateau on the stress–strain curve in some materials. |

Identified using the elastic region slope and offset method when no clear yield point exists. |

|

Materials Showing It |

Mild steel and some low-carbon steels show a distinct yield point. |

All materials have yield strength, even if the yield point is not visible. |

|

Measurement Method |

Directly observed from the stress–strain curve where yielding begins. |

Calculated using the 0.2% offset method or equivalent when the curve has no sharp yield. |

|

Nature |

A single, sharp point. |

A broader, defined strength value for engineering use. |

|

Usage in Design |

Not always reliable, as many materials don’t show it. |

Widely used for material selection and design calculations. |

Factors Affecting the Yield Point

Material Composition

Various elements alter the strength and bonding properties within a material. Carbon, chromium, nickel, and manganese increase resilience against deformation, thus enhancing the value of the yield point. Impurities and low-strength elements lower the strength. The composition determines when plastic deformation occurs.

Grain Size

Grain size, geometry, and distribution have a large effect on yield. Fine grains reduce the chances of dislocations, thus enhancing yield strength, while large grains make it easier for slip. Variables such as precipitates, inclusions, and dislocation distribution affect the ease with which the material goes from an elastic to a plastic phase.

Temperature

Yield point reduces at higher temperatures because the atoms vibrate more and deformation becomes easier. At low temperatures, atomic motion becomes less, which enhances strength and postpones the onset of yielding. Large temperature changes may also influence ductility and the value of stress required for deformation.

Strain Rate

A higher rate of straining implies faster deformation, leaving less time for the movement of dislocations, thus making the value of the yield point high. A lower rate of straining implies a slower rate of deformation, allowing for easy movement of dislocations and thus low yield strength.

Heat Treatment

Grain size and microstructure are the processes, changed by annealing, quenching, and tempering, that directly affect the value of the yield strength. Annealing lowers the yield point as a result of softening, whereas quenching and tempering enhance microstructure and increase resistance to plastic deformation.

Conclusion

The yield point brings the difference between temporary and permanent deformation. Yield value is very important in the design of all the components, and more so those components that are subjected to loads where failure or permanent deformation cannot be achieved. Yield point is susceptible to numerous variables, e.g., material composition, temperature, grain size, heat treatment, etc. The selection of the best material should therefore be done well and tested.

FAQs

-

What is the meaning of yield point?

The stress rate at which a material starts to plastic deform is known as the yield point. After this stage, the material will no longer go into its original shape once the load is taken off.

-

What is the formula for the yield point?

The yield strength is determined by F/AF/AF/A, which is a formula of stress at which the material starts to deform plastically and is not a distinct yield point formula.

-

Why is the yield point important?

A very significant property is the yield point, as it is the maximum stress to which a material can be subjected without permanent deformation. It is applied by engineers to develop structures, select materials, and prevent collapse when structures are under working loads.

-

What is the yield point in a stress-strain curve?

The yield point in the stress-strain curve is the point at which the elastic deformation is changed into plastic deformation. It is frequently manifested by the emergence of a drop or plateau in such materials as mild steel, and this signifies the beginning of permanent deformation.

-

What is the SI unit of yield point?

The SI unit of yield point (yield stress) is Pascal (Pa). Practically, it is commonly expressed in megapascals (MPa) due to the large values involved.

-

What happens after the yield point?

Beyond the yield point, the material attains the plastic region that has a permanent deformation with small stress increments. Eventually, the material becomes of ultimate tensile strength, and then it fractures if it is loaded.